Cinema, from its very inception, has been about magic. The simple illusion of motion, projecting still images rapidly to create life, was perhaps the first great special effect. Ever since those flickering beginnings, filmmakers have chased the impossible, using visual effects not just to enhance reality, but to build entirely new ones. It’s a journey I find endlessly fascinating, tracing the path from simple in-camera tricks and painstaking practical effects to the sophisticated digital wizardry that defines so much of modern filmmaking. How did we get from Georges Méliès’ trip to the moon to the photorealistic worlds of today? Let’s explore this remarkable evolution.

The Age of Illusion: Early Tricks and Practical Mastery

Long before computers entered the picture, filmmakers were masters of illusion, employing techniques that feel both ingenious and charmingly analogue today. Think back to the earliest days – the simple ‘stop trick’ used as early as 1895 to simulate a beheading, a technique pioneered by Alfred Clark and later perfected by Georges Méliès, the ‘Cinemagician’. Méliès truly embraced the fantastical potential of film, using techniques like multiple exposures, dissolves, and hand-painting frames to create dreamlike visions in films such as *Le Voyage dans la Lune* (1902). These weren’t just technical exercises; they were foundational steps in establishing cinema’s unique ability to visualize the imagination. It’s incredible to consider how these early experiments laid the groundwork for everything that followed.

The craft evolved rapidly. Techniques like matte painting, often executed on glass plates by artists like Norman Dawn as early as 1907, allowed filmmakers to extend sets and create grand vistas without building enormous structures. Charlie Chaplin’s *Modern Times* (1936) used this to great effect. Stop-motion animation brought inanimate objects and mythical creatures to life, reaching astonishing heights in *King Kong* (1933) and later perfected by the legendary Ray Harryhausen in films like *The 7th Voyage of Sinbad* (1958) – the first stop-motion feature in full colour – and the unforgettable skeleton battle in *Jason and the Argonauts* (1963). I still marvel at the artistry and patience involved in those sequences! Alongside these visual tricks, physical effects – mechanical props, miniatures, pyrotechnics, and sophisticated prosthetic makeup like that seen in *An American Werewolf in London* (1981) – brought tangible realism and visceral thrills to the screen. Even disaster films of the 70s, like *The Poseidon Adventure* (1972), pushed the boundaries of model work and practical effects to deliver spectacle.

The Digital Dawn: Pixels Begin to Paint

The late 1970s and early 1980s marked a seismic shift, the first tremors of the digital revolution. While still rudimentary, computers began to creep into the filmmaking process. Who could forget the first glimpses of computer-generated imagery? 1973’s *Westworld* featured the first 2D CGI – that pixelated ‘robo-vision’ representing the android’s perspective. It seems basic now, but it was a glimpse into the future. Just a few years later, its sequel *Futureworld* (1976) showcased the first use of 3D computer graphics. And then came *Star Wars* (1977). While celebrated for its groundbreaking model work and optical compositing, it also featured crucial 3D wireframe graphics for the Death Star briefing sequence, created by Larry Cuba. This wasn’t just illustration; it was using computers to visualize complex spatial information for the narrative. Ridley Scott’s *Alien* (1979) also utilized wireframes, but it was *Star Wars* that truly ignited the imagination.

The early 80s saw the potential explode, albeit often in stylised ways. Disney’s *Tron* (1982) wasn’t just set inside a computer; it was one of the first films to extensively use 3D CGI, bringing its unique digital world to life with over fifteen minutes of computer-generated sequences, including those iconic light cycles. It was a bold statement about the aesthetic possibilities of the new technology. That same year, *Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan* featured the ‘Genesis sequence,’ one of the first fully CGI sequences in a feature film, simulating planetary creation. And while *Blade Runner* (1982) relied heavily on masterful analogue techniques like matte paintings and miniatures to create its stunning dystopian vision, its visual futurism resonated deeply with the burgeoning digital age. These early steps, though sometimes technologically limited, were crucial in proving the concept and paving the way for more integrated digital effects.

The CGI Revolution: Realism Takes Hold

The late 80s and early 90s were where things truly kicked into high gear, moving CGI from novelty to necessity. A pivotal moment I often reflect on is the stained-glass knight in *Young Sherlock Holmes* (1985). This marked the first attempt to seamlessly blend a CGI character with live-action footage, a feat achieved by a team at Lucasfilm that included a young John Lasseter, who would later co-found Pixar. Then came James Cameron’s *The Abyss* (1989), which gave us cinema’s first convincing CG water effect with its mesmerising pseudopod creature. Created by ILM, this sequence required immense effort and collaboration, pushing the boundaries of simulating organic forms and interaction with the real environment. This quest for realism culminated spectacularly in Cameron’s next sci-fi epic, *Terminator 2: Judgment Day* (1991). The liquid-metal T-1000, with its astonishing morphing capabilities, wasn’t just a technical marvel realised partly on personal computers; it genuinely popularised CGI, making audiences everywhere ask, ‘How did they *do* that?’

And then, of course, there was *Jurassic Park* (1993). It’s hard to overstate its impact. Steven Spielberg masterfully blended state-of-the-art animatronics by Stan Winston with groundbreaking CGI from Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) to bring dinosaurs to life with a terrifying and awe-inspiring realism never before seen. Those six minutes of CGI, seamlessly integrated with practical effects, didn’t just revolutionise creature features; they fundamentally changed the industry’s perception of what CGI could achieve, moving it from a supporting tool to a potential headliner. This era also saw the birth of the first fully computer-animated feature film, Pixar’s *Toy Story* (1995). Beyond its technical achievement, *Toy Story* proved that CGI could deliver emotionally resonant stories, paving the way for the dominance of computer animation. Simultaneously, films like *Casper* (1995) broke ground by featuring the first fully CGI lead character interacting extensively with live actors, further normalising the presence of digital creations.

Refining the Craft: Motion Capture, Massive Battles, and Invisible Art

With CGI firmly established, the late 90s and 2000s focused on refining techniques and expanding scale. Paul Verhoeven’s *Starship Troopers* (1997) demonstrated the ability to stage massive, complex battle sequences populated by hordes of CG creatures, influencing countless action and fantasy films that followed. Techniques like photogrammetry, used by David Fincher in *Fight Club* (1999) to create 3D models from photographs, offered new ways to manipulate environments. And who could forget the visual language introduced by *The Matrix* (1999)? Its iconic ‘bullet time’ effect, a stunning blend of multiple cameras, CG interpolation, and wire work, wasn’t just visually arresting; it fundamentally altered how action sequences could be conceived and perceived, proving CGI was an integral part of cinematic language.

The quest for believable digital humans continued, reaching an early peak with *Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within* (2001), which featured a near-photorealistic digital protagonist. While the film itself wasn’t a commercial success, it highlighted the immense technical challenge and ambition involved. A more impactful breakthrough came with motion capture (mocap). Peter Jackson’s *The Lord of the Rings* trilogy (starting 2001) was revolutionary in this regard. Andy Serkis’s performance as Gollum, captured and translated into a fully realised CG character interacting seamlessly with live actors, proved the dramatic potential of mocap. It wasn’t just about movement; it was about capturing performance. Weta Digital’s work on the trilogy also pioneered the use of software like MASSIVE to generate thousands of AI-driven digital soldiers for epic battle scenes, creating a sense of scale previously unimaginable. Later, films like *The Polar Express* (2004) experimented with capturing entire performances via mocap, though the aesthetic results often sparked debate about the ‘uncanny valley’.

The Age of Integration: VFX as the New Normal

James Cameron, never one to shy away from pushing technological boundaries, delivered another landmark with *Avatar* (2009). This film represented a culmination of previous advancements, particularly in facial capture technology. Weta Digital developed sophisticated rigs that allowed the subtle nuances of actors’ facial expressions to be translated onto their Na’vi counterparts, finally overcoming the ‘dead eye’ problem that had plagued earlier digital characters. Cameron himself stated that the facial performance capture was a bigger breakthrough than the film’s much-hyped 3D. *Avatar* truly blurred the lines between live-action and animation, creating an immersive, almost entirely digitally constructed world that felt tangible.

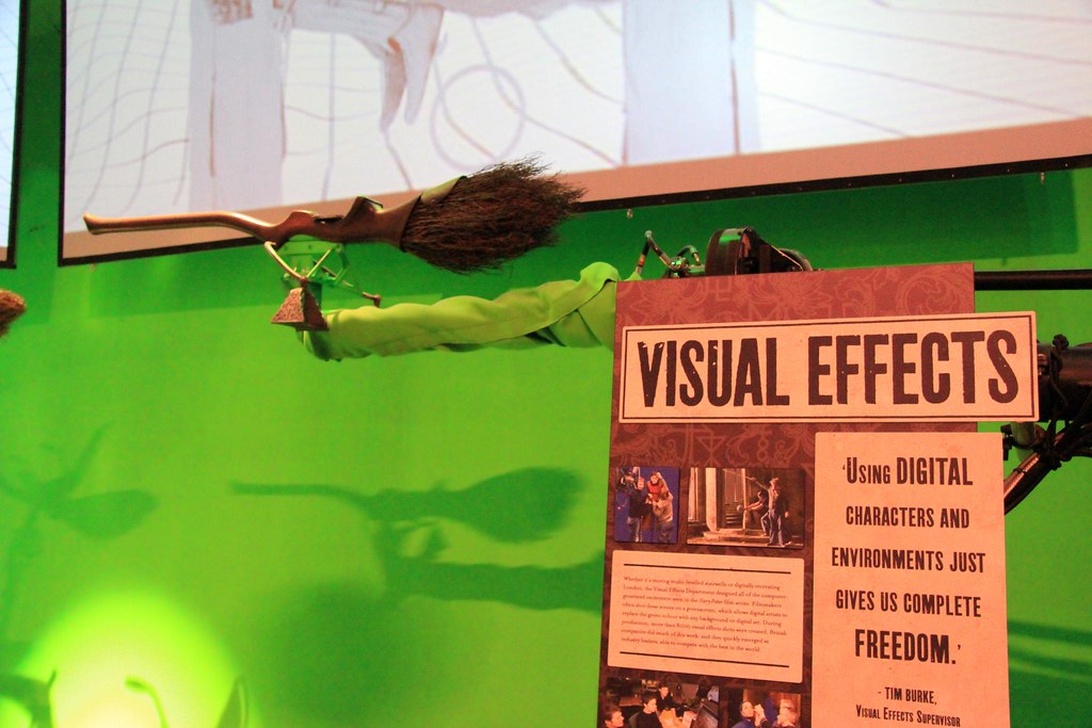

Today, visual effects are ubiquitous. The distinction between a ‘special effects movie’ and any other film has become increasingly blurred. As media studies professor Julie Turnock notes, even films outside the blockbuster realm routinely employ digital tools for everything from subtle environment enhancements and wire removal to complex character work and world-building. Digital compositing, chroma key (green screen), digital colour grading – these are now standard tools in the filmmaker’s arsenal. This integration reflects a fundamental shift discussed by Lev Manovich in ‘What is Digital Cinema?‘, where live-action footage becomes just one element among many, manipulated and composited within the computer. Film has, in a sense, returned to its roots in manual creation, but on an infinitely more complex, pixel-by-pixel level – moving from a ‘Kino-Eye’ that records reality to a ‘Kino-Brush’ that paints it.

This widespread adoption raises interesting questions. Has the pursuit of photorealism, championed by effects houses like ILM with their influential ‘documentary camera’ style, led us to undervalue more stylized or overtly artificial effects? I sometimes miss the tangible artistry of Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion, where you could appreciate the craft precisely *because* it wasn’t perfectly real. Is something lost when the magic becomes invisible? Furthermore, the dominance of VFX-heavy blockbusters reflects broader industry trends, prioritizing spectacle and franchise potential. While digital tools have also democratized filmmaking to some extent, allowing independent creators access to powerful effects software, the high end of VFX remains a complex and resource-intensive endeavor, often involving hundreds of artists across multiple studios.

Beyond the Screen: Where Does the Magic Go Next?

Looking back, the evolution of visual effects is nothing short of breathtaking. From Méliès’s cardboard moon to the intricate digital universes of today, the journey reflects cinema’s constant reinvention and its enduring power to transport us. We’ve seen technology repeatedly catch up to imagination, enabling stories that were once impossible to tell. Techniques born in the realm of science fiction have become commonplace across all genres. The line between the ‘real’ and the ‘created’ on screen is now finer than ever, often completely imperceptible. What frontiers remain? Real-time rendering engines used in video games are increasingly finding their way onto film sets, allowing filmmakers to see complex effects integrated live during shooting. Advances in AI promise further automation and perhaps entirely new ways of generating visuals. Will we reach a point where any imaginable image can be conjured instantly? And more importantly, how will filmmakers use these ever-expanding tools to tell compelling stories, evoke emotion, and continue the grand tradition of cinematic magic? The screen may be digital, but the quest for wonder remains timeless.